"The milk ran dry" and possibility at the edge

Musings on C Pam Zhang's "Land of Milk and Honey" and plant-based alternatives

Happy New Year pals!

foodstuff is a free reader-supported publication that releases new material twice monthly. To receive one essay and one veggie-centred recipe right to your inbox, consider becoming a subscriber. If you’re already a supporter, thank you, thank you, thank you for being here with me!!

If you missed the last issue of foodstuff, check it out: Fighting at the Table

I’ve been thinking about it for weeks, this moment from C Pam Zhang’s Land of Milk and Honey when the milk runs dry.

In a not-too-distant future, wealthy elites retreat to their private mountaintops with the world’s most sought-after seed reserves and biotechnologies, leaving the rest choking and starving under a thick fog. An unnamed chef, trained in French cooking is restricted from returning to her country of birth due to racial politics. With no other options for refuge she takes a job in the Land of Milk and Honey, a country high in the Italian Alps owned by a powerful man and his visionary daughter, and inhabited entirely by employees working on ultra-secret biotechnological projects. The chef, with the help of her employer’s daughter, Aida, is tasked with building menus and feeding her employer’s powerful friends, using ingredients, dishes and flavour to draw more wealth and power to that country— the only place on earth where one may still taste poulet de Bresse and hear cicadas, or so it may seem.

While the books is layered and complex, slyly touching a range of topics from climate change to nationalism to white supremacy, I read the culinary mandate of the country as replicating a familiar culinary hierarchy. The chef had to be trained in French cooking. Her employer had insisted upon it in the job description.

At the perceivable edge of the world and at the cusp of a new culinary future, its French flavours that will be carried forward. For all her employer’s ambition and for all of Aida’s scientific genius, both dismiss entire culinary traditions, methods, and with them, entire ecological worlds of possibility and flavour.

In a 2019 article for Mold Magazine Arielle Johnson wrote about flavour, outlining how everyone’s experience of flavour is unique, shaped by what they taste and smell, but also by how their sensory worlds inform and are informed by memory. There are annual rituals as well as “mundane” daily meals through which certain tastes and smells bind to a sense of home, are repeated and repeated and repeated over millennia, with generative adaptations made based on resources, migration, climate change and so on, that burrow under the skin.

Johnson’s work on flavour marks the ways that the Land of Milk and Honey uses food as a tool to accrue and maintain great influence. By focusing their attention on reproducing flavours that appeal to the world’s elites while also cultivating a breeding program dedicated to maintaining the most perfect, delicious and efficient species, the country aims to secure itself as supreme arbiter of taste and reproduce into a new world the same old hierarchies and power dynamics that enabled the fog in the first place.

However, this single-minded pursuit spectacularly fails to account for the defiance of people and planet. While conditions are poor under the fog, life persists.

On a rare trip off the mountain the chef and Aida eat a transformative Jain bing sold by a street vendor. They are shocked when city kids turn their noses up to their priceless mountain apples, opting instead for dusty mystery sandwiches. To the chef, those sandwiches hold a delicious secret: “I didn’t pity the children. Suddenly I envied them their knowledge of something better than apples, than milk, than honey” (190). In having been deemed disposable, those who survived have discovered other flavours with which to shape their lives and quell their appetites. To the chef, the bing and the sandwich represent survival and endless potential.

This is what is at stake in the novel: worlds of flavour and possibility.

This is what brings me back to the milk.

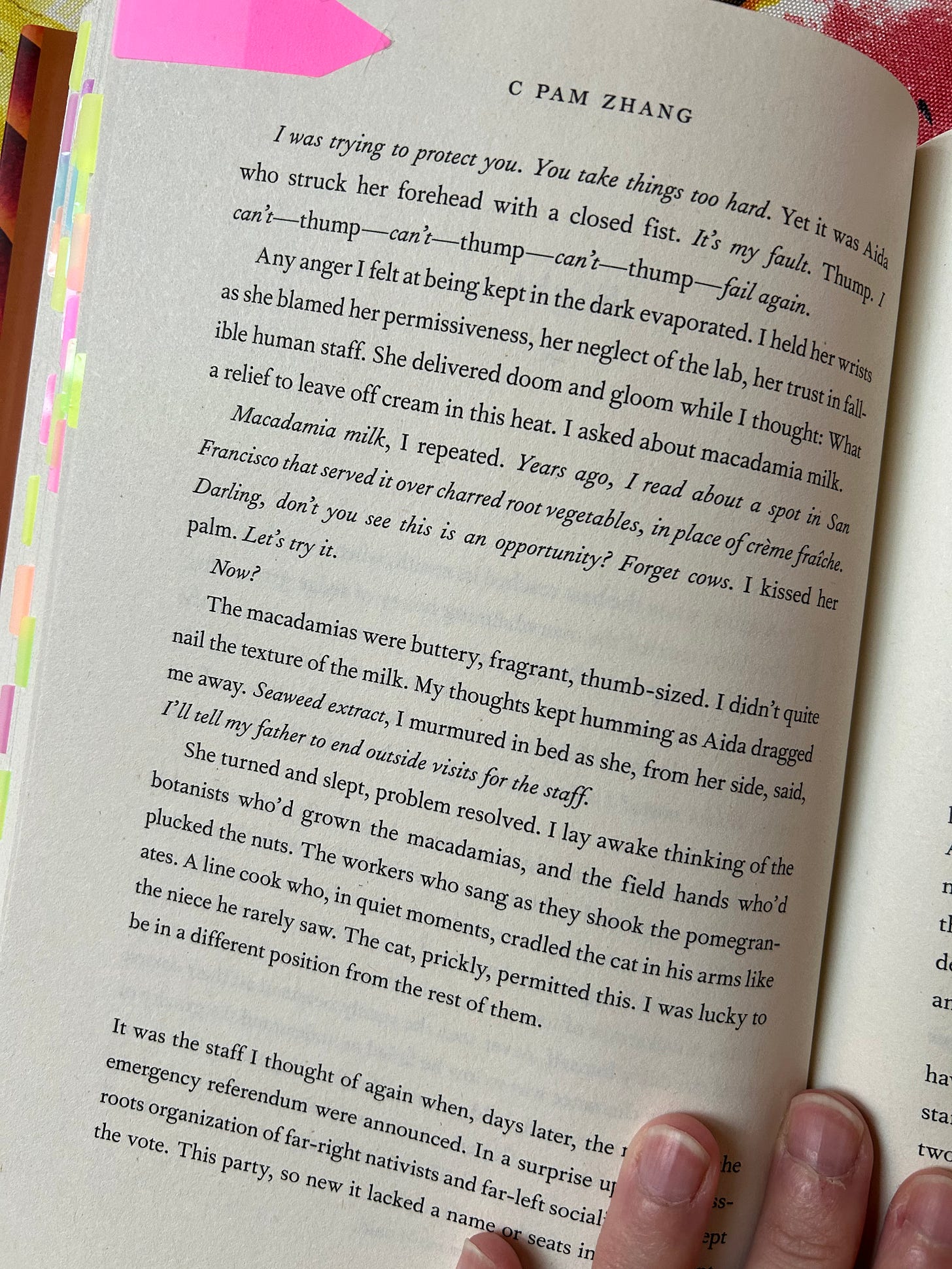

When one of the country’s employees accidentally tracks in a novel strain of foot-and-mouth after a family visit off-mountain, the country’s entire herd of cows must be slaughtered. While Aida has kept frozen cow embryos to safeguard the future, there will be no milk for at least a year. Inspired by a restaurant she once ate at in San Fransisco, the chef suggests macadamia nuts in place of milk, and enthusiastically starts dreaming up an alternative to dairy. She sees the absence of milk as a creative opportunity, as generative, not catastrophic. Aida, the science protege and visionary, cannot:

The macadamias were buttery, fragrant, thumb-sized. I didn’t quite nail the texture of the milk. My thoughts kept humming as Aida dragged me away. Seaweed extract, I murmured in bed as she, from her side, said, I’ll tell my father to end outside visits for the staff. (Zhang 128)

The milk issue effectively sums up the ideology of the mountain as one rooted in utility, control, and power. There is a fearful rejection of unruliness and unpredictability as well as the creativity necessary for making livable futures. To avoid a contaminated gene pool that may lead to less desirable reproductive outcomes for cattle (foot and mouth may cause reproductive issues and low milk yields in cattle but does not itself necessarily kill cows) an entire heard must be slaughtered. Moreover the contamination is framed as human failure, a failure on part of the staff (and a low-positioned member at that), who must also bear the weight of the country’s decisions on the matter. Like the cattle, the staff must produce relentlessly, only for the country, until deemed no longer useful. This, Aida sees as the only way.

Without spoiling the book, I’ll say that I loved the way it played with questions relating to technology and nature without falling into the trap of technology vs. nature. I like how it allowed for many layered tension to exist at once. I like how it posed questions about what it means to be a visionary, and how food’s cultural, economic, ecological, and social associations are used in framing these questions: A visionary for whom? For what kind of future?

Indeed, these kinds of questions have been posed in the context of plant-based alternatives, which are increasingly framed as singular solutions to the world’s most pressing food issues. I certainly think of the work of Alicia Kennedy, who writes in her book No Meat Required, “we know what the planet needs, and it’s the radical restructuring of land use…We know what the people need, which is self-determination with regard to farming for the Global South, as well as for the Black and Indigenous people upon whose lands the United States and other nations settled…Instead, we’re getting steaks made in a lab. Who asked for this?” (151).

Last month I saw food personalities begin posting about EVERY Egg, which made its exclusive debut at Eleven Madison Park in New York City, a three-star Michelin restaurant considered among the world’s best. EVERY Egg claims to “[fulfill] the extraordinary promise of the humble egg but with even more benefits.” Despite vegan cooks, bakers and those allergic to eggs having been increasingly creative in their pursuit of many viable “eggs,” using all manner of ingredients from legumes, seeds, starches, bean water, etc. to achieve impressive feats (and often at affordable prices), these community-based contributions are not considered innovative. Certainly not as innovative as an “egg without the hen,” “without the production variability, disease risk, and high environmental impact of animal agriculture,” and with a little TM at the end of it’s name.

In my mind, the question of how to reproduce the egg as plant based isn’t the most important, especially not in the context of environmental preservation, which is the context EVERY Egg claims to speak to. If the world must have eggs, what conditions are necessary to make consuming eggs sustainable? Maybe recognizing that production variability is an inevitability when dealing with living beings? Maybe eating fewer? Maybe sourcing them more intentionally from folks who treat their hens as more than their reproductive potential?

Why are these kinds of questions not framed as “visionary” ones?

Like I’ve said before, I’ve enjoyed and have been intrigued by the so-called solutions to environmental and animal welfare issues packaged in trendy hues, but when I think about what kind of vision they support broadly, and not just in my individual eating world, I’m troubled. While it’s not worth nothing that I can bring a pack of plant-based burger to my dad’s for him to grill up— something he always enjoyed doing for me before I stopped eating meat— I’ll remain troubled by how these named innovations are framed as the singular future, not only of plant-based food, but food in general. I’ll remain troubled by Aida’s words: I’ll tell my father to end outside visits for the staff. (Zhang 128).

Love this! I was of course watching the Every Egg with eyes very squinted... a wild affair to watch...