“Reasonable Profitability” and other garbage from the grocery ghouls of Canada

A short and grumpy analysis

First off, I want to say a very big thank you for the thoughtful comments that you left on my last essay “On Flour and the Last of Us.” They’re so good and I love engaging with you in these ways!

foodstuff is a free reader-supported publication that releases new material twice monthly. To receive posts and recipes right to your inbox, consider becoming a subscriber. If you’re already a supporter, thank you, thank you, thank you for being here with me!!

It took me two days to get through the full video of Canada’s big three grocery CEOs getting “grilled” on grocery inflation by Members of Parliament on the Standing Committee for Agriculture and Agri-Food.

I, like most, find Galen Weston Jr. (Loblaw Companies Ltd.) especially insufferable. Michael Medline (Empire Company Ltd.) and Eric La Flèche (Metro Inc.) are not much better, but Mr. Weston has a 15 year track record of assailing the country through President’s Choice ads, trying to appear a mere commoner in his little buttondown, all the while sitting on more money than God.

Image description: Michael Medline, president and CEO of Empire Co. Ltd., left, and Galen Weston, chairman and president of Loblaw Cos. Ltd., wait to appear as witnesses at the Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food investigating food price inflation in Ottawa, Wed., March 8, 2023. (Photo from: Spencer Colby, The Canadian Press)

Another reason this video was so hard to get through was that the central question many are currently facing, that is, “how can someone afford to eat today, tomorrow, and beyond?” remained–predictably, upsettingly– unanswered.

To be clear, the problem of food insecurity and food price inflation is a big one that requires a food systems approach. This means that we can recognize the problems caused by large corporate grocery chains dominating the market– they are big and worthy of critique– while also acknowledging the inadequacies of public policy at addressing problems related to food and housing security.

In short, Loblaw, Empire, and Metro hoard a massive amont of power in Canada’s food system and, as I address below, this has proven to hurt farmers, growers, workers, and consumers. These enterprises should be held accountable. At the same time, chastising these corporations for doing what corporations do is not meaningful in the way it must be to feed a hungry public.

Grocery in Canada

For those who’ve not had the chance to follow, or for those who are coming to this essay from other locations, here is some context that helps explain my (and many other folks’) bitterness towards Loblaw, Empire and Metro.

For one, Canada’s grocery industry is often described as an oligopoly because the market is dominated by such a small number of sellers, namely, the three called to the House of Commons, who collectively control over 50% of market shares (per 2021 numbers; Medline contends that it’s 47% of market shares and, since this is in alignment with other parts of the world, that it’s totally fine for the three largest grocers in a country to dominate that market??). It is this level of control that enabled the bread price-fixing scandal of 2018 (which has still not been answered for) whereby the Competition Bureau alleged that the senior officers of Canada Bread (now a Grupo Bimbo subsidiary), and Weston Foods, (now a sister company to Loblaws under parent George Weston Limited), colluded to boost bread prices, and later strong-armed retailers to increase their prices in tandem.

Also related to accrued power, Loblaw, Empire, and Metro all announced and cut the $2 per-hour pandemic Hero Pay at the same time in June 2020, with many arguing this was a calculated and coordinated decision of callus disregard for grocery workers, as well as an unsettling example of the expreme power these enterprises collectively maintain over industry standards.

Loblaw and Metro (and Walmart Canada) have been accused of bullying suppliers to pad their bottom lines. While they argue this is for “customer protection,” it is important to consider how such tactics work against small growers and suppliers who have faced increase costs as a result of inflation, but that are not seeing the same profit margins as Loblaw and Metro.

It is also worth noting that there is a considerable amount of frustration among the public regarding the end of the No Name price freeze, which went into effect mid October 2022 and concluded January 31, 2023. By “locking in” the prices of their most economical food brand, Loblaw boasts that it saved consumers “close to 45 million dollars.” Many have asked why this ending was necessary at such a critical moment for those struggling under inflation, especially if, as Weston claims, the bulk of Loblaw’s profits come from pharmacy and definitely not the No Name Brand.

The Subtext: Profits>People

The instances I’ve listed above have understandably pissed people off. We read the subtext for what it is– that profits remain more important than people in the eyes of Big Grocery.

Take the price freeze for example. By stating that they saved consumers close to 45 million, Loblaw is trying to reframe a marketing/ PR decision (that brought more customers into their stores who likely purchased things other than No Name) as a benevolent act of charity in which they’ve offered their customers nearly 45 millon of their income.

The frustration caused by this kind of rhetoric– that Loblaw is a benevolent overlord– is expressed helpfully by

Dr. Sarah Duignan, who writes about a trip to her local Zehrs (a Weston owned grocery chain in Ontario):“The rage builds inside me each week I take another trip in, only to find a new display or addition to the store that reminds us all that the food inflation is beyond our control. But this one, displayed so proudly as if doing a favour or trying to trend with younger generations and show that the Westons get it felt particularly insulting.”

Many are feeling the rage and insult that Duignan articulates– the rage of injustice that is stoaked by “business as usual,” which manifests here and all over the Committee meeting as an artificial concern for consumers that’s rooted in self-promotion.

It’s like Duignan anticipated the PR strategy going into parliament. That Weston, Medline and La Fléche “get it,” that it’s a “hard time for Canadians,” but not something they can do anything about, was hammered home by their performances of relatability and understanding, with undertones of persistent self-congratulation and defensiveness.

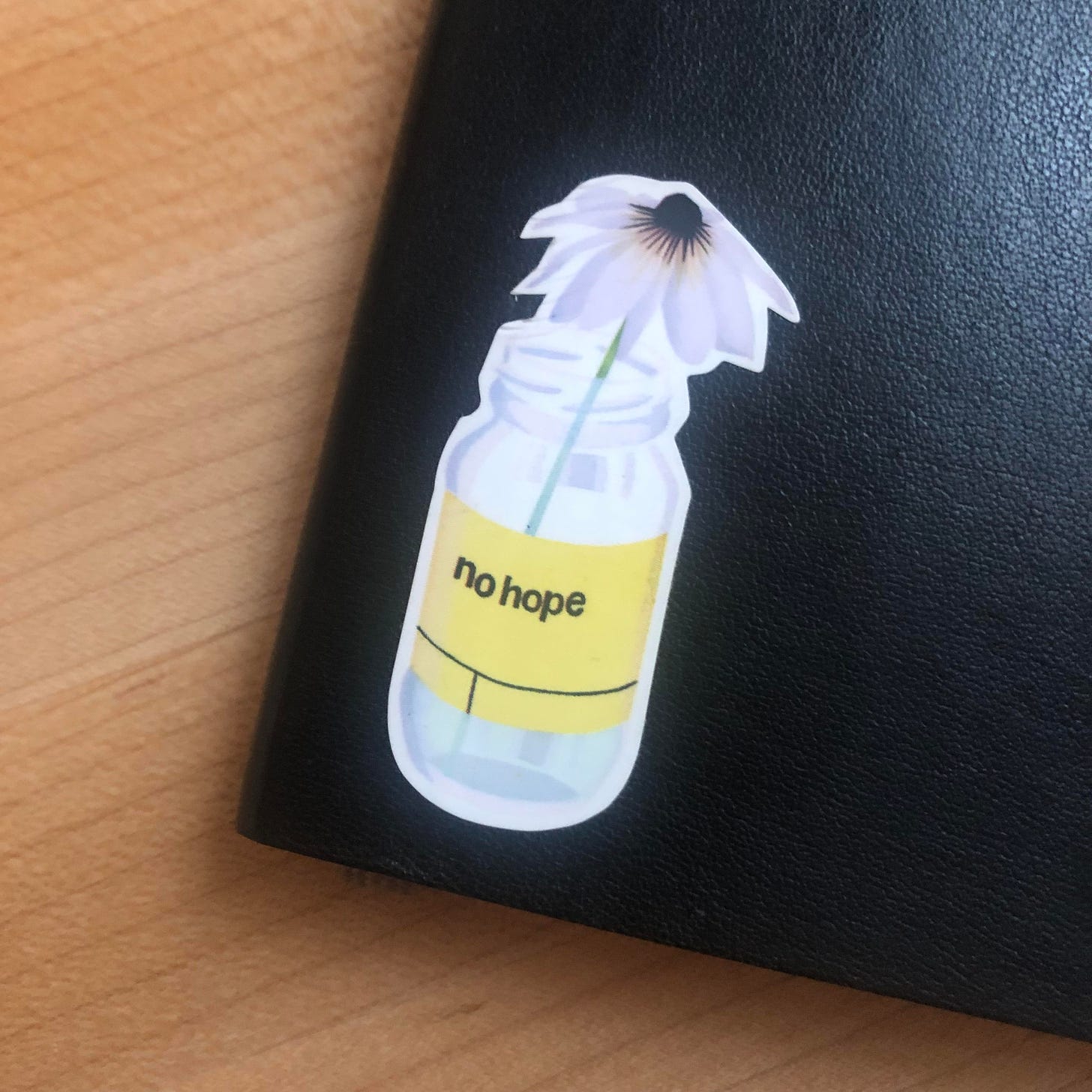

Image description: A sticker on a black notebook. The sticker evokes a No Name pickle jar, yellow label with black writing reading “no hope.” A daisy sits in the jar.

Weston told (what is very likely a completely fabricated) story about a conversation he had with a customer who was upset about grocery inflation. He suggested that she walked away from their exchange, where he explained grocery prices to her, offering forgiveness. The tactic here is to imply that those of us who don’t “get it,” as this fake woman did, are just too foolish. Hilariously, he did not offer to the committee any glimpse into the explanation he gave to have such an effect on this woman!

Next to Weston, who is certainly portrayed as the villain of grocery in the media, Medline played Man of the People, evoking his East Coast roots, and expressing his concern for farmers while making sure to mention on multiple occasions (and with deliberate puncuating pauses) that at Empire Company they like to call their staff “teammates.” He then went on to evade the question about why plans to reinvest in new stores take priority over investing in current “teammates.”

To be honest, La Flèche Zoomed in and got off pretty easy but was also quick to insist that at Metro they were simply passing along the high prices being charged by suppliers, and were therefore, faultless.

These examples help to illustrate a calculated strategy to evade responsibility while appearing empathetic. It is worth noting that NONE made any serious commitments to meaningfully address the concerns of the public or invest profits into supporting staff.

Their responses to the questions posed were intended to salvage their public image, not to provide useful or transparent answers.

“Reasonable Profitability”

When probed about unprecedented profits (a complicated topic, I know, given these numbers include grocery and pharmacy and other streams depending on which enterprise we’re talking about), all three agreed in one way or another, that “reasonable profitability” was essential to good business.

In response to Jagmeet Singh’s question “how much profit is too much?” Weston offered a description of this “reasonable profitability” saying:

“It’s worth mentioning, you know, big numbers, in large enterprises like ours— let’s say, our profit was in and around 1.9 billion dollars last year, very big number— over 2 billion is going to be reinvested back in this country, back into supermarket, er back into new stores, to infrastructure, to creating jobs.”

Upon first glance, this might sound charitable granted it isn’t a boldfaced lie (we have no proof yet of this beyond Weston’s word). However, prod a little and you’ll find a true description of capitalism’s endless growth mentality. Indeed, it is this relationship to growth that economic anthropologist Jason Hickel asserts, “makes capitalism distinctive” from other economic systems in history (Less is More 40).

Hickel explains that it is not markets that define capitalism, rather, it is the growth mentality of capitalism that pulls “ever-rising quantities of nature and human labour into circuits of commodity production. And because the goal of capitalism is to extract and accumulate surplus, it has to get these things for as cheap as possible” (40).

Within the context of capitalism, Weston’s promise to reinvest “back into the country” and “back into new stores,” is not, nor will it ever be about feeding people or creating jobs that will support people living well. It is and will always be about this so-called reasonable profitability, which in the grocery industry–by Weston’s own data on their “big numbers” and small margins, margins which amount to 4% per grocery basket– requires a massive volume of sales, a volume that can only really be procured by their monopoly over the industry and over suppliers, and balanced also by their monopoly on labour standards within the industry.

In Conclusion

While I really do enjoy the idea of seeing CEOs actually account for the impacts of their businesses, like many, I’m also left frustrated by the ordeal of the questioning because on the one hand, the assumption that those men are agents of change has always been a false one, and on the other, their performative half-answers have proven useless, perhaps even confusing, to those coming up against a faulty food system.

To be very clear, a more just food system is not one in which Loblaw, Empire and Metro own even more market shares. It is not one in which access to food is privatized and monopolized by corporations who, by design, are oriented towards profit accumulation.

Reading

This month I finished a single collection of poetry, that is Larissa Lai’s Automation Biographies, did a bunch of re-reading for dissertation work and read too many of Loblaw’s public financial information from the last three years.

Cooking + Baking

So much Broccoli Butt Pesto, which is the recipe I will be sending out on the 15th!

Image description: A bowl of pasta covered in a green pesto sauce topped with basil and fermented chilis.

I’ve also been playing around with a vegan and gluten free variation to Eric Kim’s Gochugang Caramel Cookies! It’s not done yet but I think I’m getting there with much help from partner, who was once an excellent baker. Let me know if you’d be interested in this recipe once it is perfect!

Would love the gochujang cookie recipe variation once it's ready!!!

This is such a helpful breakdown omg, thank you

As for books: I am currently reading Hiromi Goto's Chorus of Mushrooms -- you've probably come across it in the canlit/food lit world, but if not, I would seriously recommend!