foodstuff is a free reader-supported publication that releases new material twice monthly. To receive one essay and one veggie-centred recipe right to your inbox, consider becoming a subscriber. If you’re already a supporter, thank you, thank you, thank you for being here with me!!

There’s a new vegan shop opening in the Hamilton Farmers Market that’s causing a little stir.

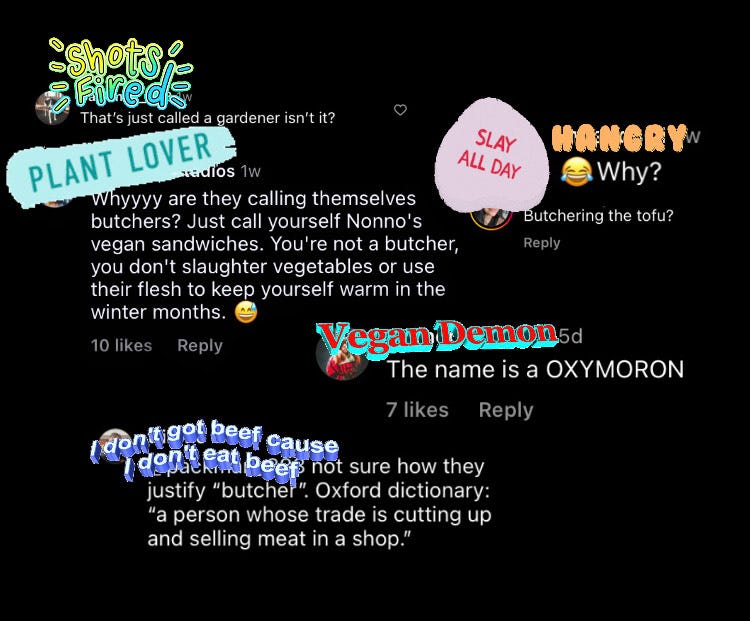

Nonno’s Plant-Based Butcher has received some coverage this past month in local papers, media outlets, and across social media, and while many are expressing excitement at the prospect of a local vegan deli, there seems to be some confusion, let’s say, over the inclusion of “butcher” in the shop’s name. Take a look:

First, claps all around to the people who took time out of their day to point out that a VEGAN shop does not actually butcher meat…

But in all seriousness, there is something about this protectiveness over the word butcher that’s got me a bit more irritated than usual (if you couldn’t already tell from this sarcastic introduction). I think it has to do with the assumption that the practice of butchery, especially the old-school Italian butchery which Nonno’s namesake invokes, is just about cutting up and serving meat, and is therefore always in opposition to a vegan ethic of care.

Before I get into the meat of the issue, I feel the need to emphasize that, as someone who refers to herself as vegan, I reject forms of veganism that assume moral superiority, that believe there is one perfect way to eat, and/or that denigrate people’s cultural practices involving meat. Those are not included in a “vegan ethic of care and non-violence” as I understand it. I also don’t think someone has to be vegan or veggie to be a mindful and responsible eater with the capacity to recognize, critique, and challenge the very real issues of industrial agriculture, which is never separate from the issue of meat consumption in the Global North.

Now into…

The meat of it

At this particular moment of climate and labour emergency it’s not a wild thing for people to question their relationship to meat, and I don’t just mean whether to eat it or not. How much meat to eat, what kind, which cuts, and from where or whom are important considerations as well.

That said, questions surrounding meat are not only questions for meat-eaters.

Though the last time I ate meat was in 2014, I still have a relationship with it in the form of my dog’s food, for example, but also… I’m made of the stuff! You are too. This means that my relationship to meat includes thinking about my relationship to my own body and the bodies of other. How human and non-human animal bodies are rendered under intersecting systems of oppression as food, as cheap labour, as disposable, etc., has much to do with meat. (For more in-depth reading on this you can start with writers like Carol J. Adams and Sunaura Taylor.)

In 2023 the problems with industrial farming for animal, worker and planetary welfare are known. In The Politics of Industrial Agriculture Tracey Clunies-Ross and Nicholas Hildyard offer a concise summation of the broad impacts of industrial food in general writing that, while industrialization “has dramatically increased yields,” mechanized systems of production have “also led to extensive rural depopulation; widespread degradation of the environment; contamination of food with agrochemicals and bacteria; more routine maltreatment of farm animals” as well as the undermining of economies and livelihoods of farmers and food workers in the Global South through unfair trading systems, not to mention the unsanctioned occupation of lands for the production of monocultures for animal feed.

In the U.S., which is a large producer and processor of meat, mechanized systems of food production rely on a so-called “unskilled” workforce. Animal agriculture and meat processing in particular is well regarded as challenging work that has been historically done by enslaved or previously enslaved folks, immigrants, and migrant workers explicitly because these groups were viewed as sources of free or cheap labor.

In a recent essay chef, educator, founder of Studio ATAO and author ofWay Too Complicated, Jenny Dorsey, traces how skill has been determined by a racist and sexist classification system that has little to do with concrete competencies and more to do with who has historically been forced to occupy certain roles. She also points out how many of these supposedly “unskilled” jobs– “cooks, domestic caregivers (childcare, elder care), farmers, janitors, cashiers, warehouse workers, and meatpacking workers, just to name a few” were named essential in the first years of COVID pandemic, with then-President Trump even signing an Executive Order to keep meatpacking plants open despite infection rates (Dorsey).

While Dorsey’s essay focuses on the U.S., it is worth noting that Canada follows a similar TEER system to articulate “high-skill” and “low-skill” work, adopted similar categorizations of “essential work” in the first years of the pandemic, and saw COVID outbreaks proliferate the meat industry.

Well-established critiques of industrial food production, including those relating to the production of meat, have not and have never come exclusively from vegans and vegetarians. This is a reality that anti-vegans love to forget, especially those who defending their consumption with careless appeals to Indigenous foodways.

In truth, a core belief bridging food sovereignty movements across Indigenous communities is that certain things cannot be commodified. Land, water, air, animals, even the health of the people are considered collective resources that require community management. Put very simply, these beliefs, and the practices they are tied to, have always been at odds with industrial agriculture, which itself relies on the commodification and dispossession of lands and bodies.

In addition, well-known omnivorous cooks and writers like Tamar Adler, Samin Nosrat, Alice Waters and countless others have expressed concerns over how animals are raised, processed and consumed while advancing socially conscious philosophies of cooking—ones that fosters responsible relationships between cooks, farmers, and the earth.

For instance, in her chapter “How to Be Tender” from An Everlasting Meal, Adler is adamant that the factual details of ones relationship to animals killed for food matters– how animals are treated both in life and death are not inconsequential, rather, these facts must guide consumption should one choose to eat meat. Adler notes, consumers in the Global North are taught to think about meat as individual cuts as opposed to whole animals, writing “There’s not yet a cow with an eternal supply of steak, a pig that is all loin, or a chicken that is all boneless white meat” (156). Here, Adler underscores the reality that producing favourable cuts of meat in the quantities people want them is not a sustainable practice, nor does it minimize harm. What it does is drive up the number of animals processed per annum, which inevitably impacts people who process those animals, who raise them, who produce the food to feed them, and whose lands this all takes place on.

Butchers and their animals

Butchers like Tzuria Malpica and Dario Cecchini have also expressed their dismay at the system that disrespects animal lives. In Food for the Rest of Us, Malpica, who is a farmer and Schohetet (or a woman Kosher butcher) says that it “freaks [her] out” that “in bigger processing plants it’s just ‘raise as many animals as you can, get them as fat as you can, harvest them, do it quickly, do it precisely’” with little human interaction. “That feels like another way we distance ourselves from our food,” she says.

Like Malpica, Cecchini, who is widely regarded as the world’s most famous butcher, refuses to distance himself from the animals he butchers. In his Chef’s Table episode he speaks to the experience of visiting family farms in Italy.

He explains, in Italian, that on these farms the animals are part of the family, that every time he is in front of an animal’s death, he thinks of “the life, of the respect, of the responsibility of using everything well, of not offending this death.” Being a butcher, Cecchini says, is not living detached from animals “but beside them.” Through these assertions, he characterizes the role of the butcher (but also the cook) as that of a caretaker and undertaker. To talk about the food he makes at home and in his restaurants he begins from the emotional difficulty of his vocation, how his practice emerged from a place of pain and discomfort as well as joy, gratitude and connectivity. These complicated emotions he attributes to his love for animals as well as peasant Italian cookery and butchery traditions which use every bone well.

Of meat he says, “you’re handling a piece of life. You have to never forget that.”

Indeed, Malpica’s practice reflects complex entanglements too, following the life and death of animals most intimately. I’m linking the feature on her from Food for the Rest of Us, though please note, it may be a difficult section to watch for some as she does perform a slaughter.

In this film, she is seen feeding her animals and ushering them out of this world through their offering. She also provides opportunities for others who, like her (as a woman Schohet), may have been excluded from accessing ancestral knowledge as well as lands upon which to do that work. Malpica does this without romanticizing butchery, telling her guests how being a Schohetet impacts her body, her nervous system, how performing death is not something she takes lightly, and also how it ties her to her ancestors.

If anything, Malpica demonstrates how the process–difficult as it may be–matters in forging and nurturing responsible relations with living and departed kin. She does care, demonstrating another part of what I’m coming to understand as a spectrum of human and non-human animal kinship.

Meat-ing in between

Meat is life, or was once life. My response to this is not eating it. Adler, Malpica and Cecchini respond with care-full consumption.

Though these may seem oppositional, our consideration of meat binds us in some sort of alignment, one that’s rooted in the sticky complicity that comes from having a body that metabolizes other things. With care-full eaters I resonate more than with a vegan who abstains from animal products to pursue some ableist ideal of health and wellness, or with a meat-eater who insists on meat-eating because “bacon.”

I do wonder how the social media users commenting on Nonno’s think of meat. Or how they would respond to butchers who confront their work with an awareness of life and death that aligns more with an ethic of care and nonviolence than with that of consumer capitalism.

It’s pretty funny that people are mad about a vegan butcher shop co-opting the word butcher when really, a vegan butcher may be more aligned with traditional practices of butchery, that is, with confronting the animal–not as an absent referent rendered as steak, filet, tendon, loin– but as a whole being that must be killed in order to be eaten. There is a person doing the killing. There is an animal doing the dying. It is the recognition of these facts that, I argue, bring (some) veggies and (some) butchers closer together than apart. Certainly the response to these facts can be different, and that’s another conversation, but today I’m interested in the collisions, the consistencies, the places where collaboration can take root.

What’s your relationship to meat?

Making Do

This month’s recipe is for vegan + gluten free gochujang cookies inspired by Eric Kim’s NYT Cooking recipe. If you’d like to receive this recipe to your inbox when it becomes available on May 15th, subscribe now!

Consuming

Books I finished in April:

Never Home Alone by Rob Dunn

A natural history of the home.

The Tiger Flu by Larissa Lai

This was dissertation reading but I love this book. Speculative fiction, queer.

Essays:

“‘Unskilled’ Labor is a Myth” by Jenny Dorsey

Podcasts:

Samin Nosrat’s episode of Normal Gossip had me giggling on my morning walk.

Stephen Satterfield of Whetstone launched a new podcast called The Stephen Satterfield Show where he talks with experts and friends about food and drink.

Film:

I saw Food For the Rest of Us at The Westdale this month while devouring some popcorn. Then I slinked next door to grab two servings of Nannaa fries.

This is so insightful Melissa! Tapping into some of the historical threads and giving some context. I think, from their end, it is also a great marketing concept and getting some people talking. Cheers!

Brilliant, thoughtful analysis! I really appreciate the sentiment behind following the ethics of care that we bring to our dietary choices rather than the specificities of what we’re eating.